-Authors-

李思敏 (Victoria Li),宋经纬 (Jerry Song),谢杨依然 (Wendy Xie),赵泽洲 (Zach Zhao)

We are four recent college graduates who have spent our lives between both the United States and China. Like many others, the rapidly emerging opinions on racial issues in the Chinese American community have brought us into an iterative exercise: to catch up with the newest open letters of the day and to undertake more conversations on social media and at the dinner table. In this letter, we aim to integrate historical perspectives into the conversation and support a platform that welcomes divergent voices and strives to achieve mutual understanding.

The four of us all spent our childhoods growing up in China. After a spectrum of Chinese/American upbringings in our teenage years, we continued our college education in Baltimore, Maryland. To us, we call both the US and China our home. And like many others in a progressively globalized society, our backgrounds have been important components in the ways with which we understand ourselves and the world.

When we first came to America, we were perplexed by the existence of racial issues, perhaps because it was the first time when we ever had to deal with race. We remembered asking ourselves: how can the dreamland, which we so fondly sought to enter, possibly have such ugly problems?

Before we arrived in Baltimore, the warnings of others arrived first. “It’s a violent city.” “Watch out for the Black people.” “Be careful.” The Baltimore protests to Freddie Gray’s death in 2015 attached an even greater valence to these warnings. After we arrived, like anyone else finding themselves in a new place, we tried to absorb as much as we could. Baltimore, then, became a lens through which we deepened our understanding of racism and US history.

On the subject of historical analysis and social activism, every individual’s opinions, knowledge, and backgrounds are different. Using the term “Chinese American” to represent any kind of collective experience, therefore, is limited because it is just a nomenclative category. Recent conversations surrounding the death of George Floyd have lifted the lid to the highly heterogeneous opinions among Chinese Americans. And we believe that is valuable. It is better to see a mosaic than to see nothing. For our Chinese American peers and our parents, it is better to share our views than to say nothing. As the conversations continue, we encourage everyone to actively communicate their perspectives, listen to the disagreements, and establish a model of cross-generational communication for our Chinese American future.

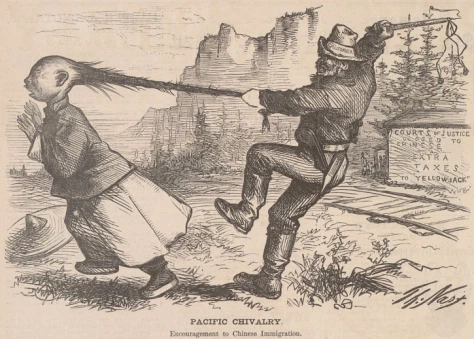

Chinese American and African American’s racial histories are not independent of each other but rather intricately connected. The most obvious example is the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. In 1865, at the end of the Civil War, the United States abolished slavery. The Southern plantation economy that relied on slavery began to decline. Hurriedly the white plantation owners convened in 1869 at the Memphis Convention and recommended that Chinese workers replace freedmen as their major labor source. They had heard stories of how Chinese workers can receive very little in compensation to work long hours under extremely difficult circumstances on the railroads across America. Soon, newspapers were reporting that Chinese workers were stealing the jobs of the American working class. Starting in 1869, exaggerated and racist newspaper articles began to fuel anti-Chinese sentiment.

Pacific Chivalry by Thomas Nast, Harper’s Weekly, 7 August 1869

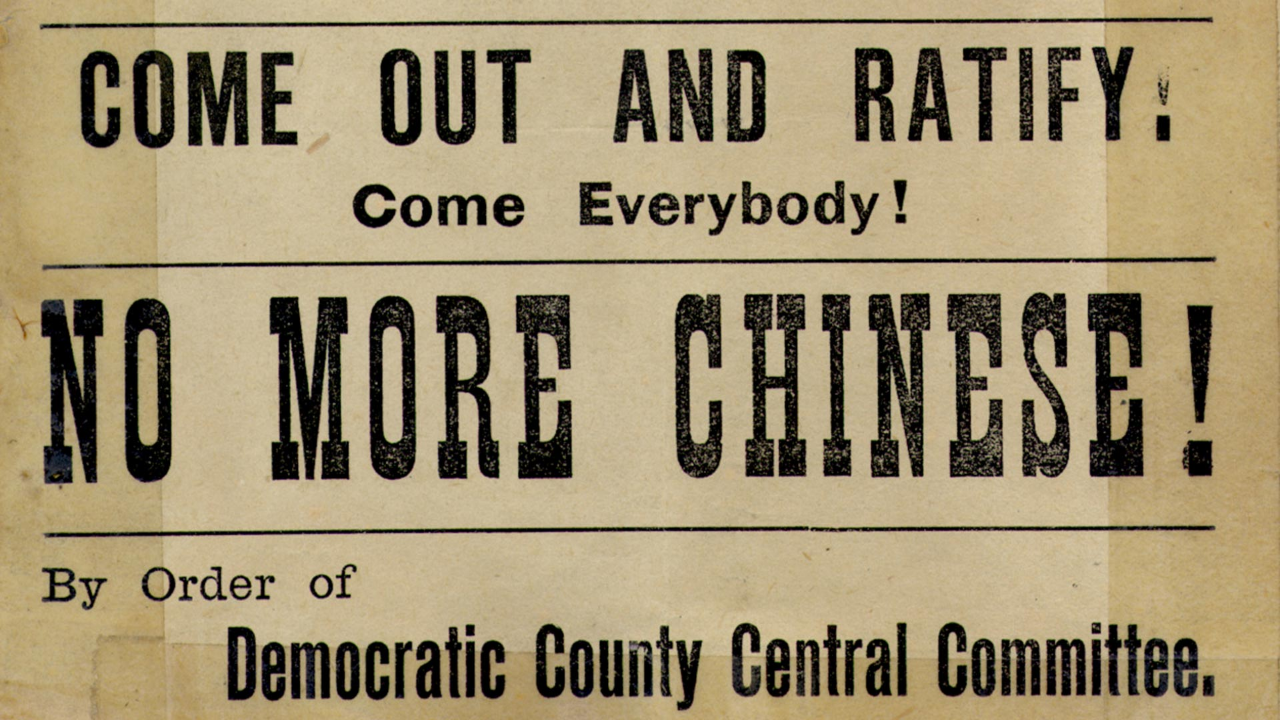

In 1876, in order to ensure that its own nominee Rutherford B. Hayes would be elected President, the Republican Party agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South, and Reconstruction completely collapsed. Once the troops withdrew, they also took away the Civil War’s hard-won victory in civil rights. Southern congressmen were able to vote again in Washington. This moment paved the way for anti-Chinese sentiments to flare up in Washington governance (to be sure, both parties ran on blatantly anti-Chinese platforms).

Thus, the formation of the most egregious anti-Chinese legislation in America was built on anti-Blackness. The Chinese Exclusion Act was more important to senators from the Western states, which had a vast majority of the US Chinese population. Senators from the Midwest and the South also supported the Chinese Exclusion Act, despite some of them never having even seen a Chinese person. They knew that if they facilitated the exclusionary atmosphere in supporting the Western senators, their own exclusionary policies, namely to suppress the Black vote, in their own regions would be supported in turn.

Poster announcing the passage of Chinese Exclusion Act (PBS).

Although the Chinese Exclusion Act was abolished in 1943, the fight for equality and peace didn’t stop there. Fast-forward to 2020. Anti-Chinese and anti-Black sentiments are still cooperative in politics. Arkansas senator Tom Cotton spoke in support of the conspiracy theory that COVID-19 was a Chinese biological weapon that got out of control. By the end of May, Cotton had proposed a new legislation restricting Chinese graduate students and visiting scholars in the STEM fields from receiving visas. This is not only a race-based policy that will bar future Chinese scholars, but also one that restricts scholars who are currently in the US and have the intention of returning to China for their career. In June, Cotton published an inflammatory op-ed in the New York Times calling for the US Army to be unleashed on those who were protesting the wrongful death of George Floyd. As we write this letter on June 7th, 2020, the New York Times editorial page editor, James Bennett, has resigned from his position following the outrage to the article.

In this backdrop, Martin Niemoller’s famous words sound the alarm, reminding us about the greater system of racism in the US and the consequence of an us-vs-them mentality.

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

In our eyes, we are far from the level of equality that we thought we had. The common denominators behind the persistence of Chinese American oppression and African American oppression will be no different for the future of all racial minorities in the United States. To that end, we know our activism can’t fix everything, but we must start by challenging the voices that make this society even more divided and unequal than what it is today.

In writing this letter, we’ve also engaged in conversations with our own families and peers about the recent protests. In the beginning, one side laments “the reality facing African Americans today is really bad, but looting I cannot accept,” while the other cried “looting is really bad, but racism and police brutality I cannot accept.” Many of these conversations we took to late nights and early mornings. And amid heated disputes, we all recognized that these conversations mean the opportunity for cross-generational Chinese Americans, to understand each other, to improve the ways we communicate, and to learn more about politics, race, and society.

We aim for this letter to not just promote open discussion in the Chinese American community but also the welfare of our future, which demands greater equality and stronger cohesion among all corners of society. This is why we chose to write: to cast our voices and the voices of those who are lesser heard. The rise and fall of the nation concern everyone. For the four of us, a central core to our values comes from our debt to our parents’ sacrifice and the shared desire of all US minorities to give the next generation a better future. To honor these values, then, means doing what we can to provide our children with a fairer, more just, and more accepting dreamland.

Sincerely yours,

Victoria Li ‘20, Jerry Song ‘20, Wendy Xie ‘19, and Zach Zhao ‘18.

P.S. The authors hereby remind Johns Hopkins students, parents, and affiliates that Johns Hopkins University has begun to assemble a private armed police force on campus . We urge all readers to learn more about the race-related policies within higher education institutions.

——————

If you are interested in learning more, here are a few resources in Chinese and English which can get you started:

《反黑人情绪与种族主义》A compilation of articles in Chinese about anti-Blackness and racism(Shimo document (no need for VPN in China))

Resources and articles about Black Lives Matter movement(中英文Google Document)

Relevant organizations to pay attention to:

Chinese Progressive Association SF https://cpasf.org/

CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities https://caaav.org/

Asian American Advancing Justice (many local chapters) https://www.advancingjustice-aajc.org/

10 评论

添加您的 →[…] An Open Letter to the Chinese American Community from Four Recent Johns Hopkins Graduates Who Call C… 0 Comments […]

About your claim that Senator Cotton’ s proposal to restrict Chinese graduate students and visiting scholars in the STEM fields from receiving visas is not only a race-based policy …but…’, I have some questions for you.

First of all, since the restriction applies to Chinese scholars/students only, then it is only country based. China and many other countries belong to one single race- Asian. A country like China or Japan is a subset of race. Cotton’s proposal’ will be race based if it applies to all countries in Asia . Listen, you have to be pretty smart to get into Johns Hopkins. How could you get mixed up between a country and a race ? Were you guys on drugs, stoned or drunk ?

Secondly, you guys ever wonder why Senator Cotton wanted to impose such restriction on china, but not other Asian countries such as Japan, Korea, Vietnam,..etc ? The reasons is because the U.S. government is aware of and concerned about the Chinese spy espionage activities in the United States. As matter of fact, this is also a concern among other western countries such as Canada, UK, Australia,..etc.

I know you guys don’t believe what I said and want evidence. Well, below are two links which will give you some details .

1. https://business.financialpost.com/technology/nortel-hacked-to-pieces

2. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2019/08/inside-us-china-espionage-war/595747/

Thirdly, the racial discrimination against blacks and other minorities in the U.S. has been around for decades. If you have some grudge against USA, then the easiest way disparage her is to raise this issue of racial acrimony. And you guys were right on this count. Congratulation. On the other hand, are the any racial discrimination against blacks in China ? I know there are not that many blacks, but here is something you may want to check it out.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCea1oIKpc0&feature=youtu.be&t=136

As for the situation in Xinjiang and Tibet, I rather not to discuss it right now.

If USA is such a country with so much discrimination againt tChinese and China is so 强大, why don’t you return to your own country to continue/pursue your study or go to countries which have better diplomatic relationship with China, such as Iran, Russia , Italy, or North Korean ?

The young people just ask for a conversation and you start to criticize and lecture them with a tone of arrogance and meanness. Older generation should be more open and nice. Aren’t they? Also, why do you tell them to “return to your own country”? This is so not appropriate.

They just asked for conversation? Come on ! They were asking for sympathy

No sympathy for you opportunists

Cotton’s proposal is not race based. It is only targeting China because of concern over the Chinese spies espionage activities in U.S. Google ‘Chinese spies espionage ‘ to find out.

You guys are visa students. Wait until you get your green card before you complain.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8435033/India-says-soldiers-mutilated-beaten-death-Chinese-soldiers.html

This is for ‘温故知新有容乃大’ and those who equate ‘ anti ccp ‘ with racism

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uSAUY0Bp9UA&feature=share&fbclid=IwAR292Bhi8qHnHewjG4D9TcLIx1Lc6U49YU3WtYSDcZOqEuEGiagxnpufVWk

And yet we don’t have slaves in america. Can china say that? No. The answer is no.