2015年美国年轻国家诗人称号获得者,目前就读于耶鲁大学的黄艾琳,曾写过一首诗 ——《有感于我怎么忘了中文》。艾琳的母亲说,第一次读到这首诗,眼泪就止不住。好像二十多年的游子漂泊之心,被女儿的诗,轻柔地触摸了一下。反思年轻人对身份的探索中,如果缺乏了父母的理解和陪伴,他们是多么孤独。

正文共:3282字

预计阅读时间:9分钟

撰文:月下谷堆

视频字幕:Jing Liu

—— 黄艾琳

在海外华人二代的成长过程中,最重要,也常常最容易被父母忽略的,就是身份认同的问题了。而身份认同很重要的一点,就是对自我和对族群的认知程度和从属性。而这个看不见摸不着的抽象概念,可能会影响孩子们的终生幸福。

华二代从小生活在两种文化中,照说有得天独厚的双重文化滋养。但外面说英文,家里吃中餐,泾渭分明,并不融合。学校里的美国历史文化中,鲜有亚裔美国人的影子;周末中文学校的听说读写中,也没有强调父辈的文化自信。父母身为异乡人辛苦打拼,他们望子成龙,关注的是孩子的学业,很少在家里分享自己移民生涯的点点滴滴;孩子们土生土长在美国,他们黄皮肤的长相,免不了要面对社会固有的“模范亚裔”刻板印象。

两代人共同经历中西文化冲突,却呑咽着不同的滋味。越来越多的人开始探讨身份认同和文化融合课题。2021年2月,在新泽西“父母子女教育俱乐部”(PCE,Parents And Children Education Club)举办的月会上,一段读诗的录像, 触动了两代人的心。

黄艾琳2018年5月在纽约 Urban Word 读诗会上朗诵自己作品的录像。

录像播出短短几分钟, 留言纷至沓来......

“我以前给儿子读过这首诗,边读边流泪,孩子问我怎么了。”

“我哭了!”

有一位妈妈,之前还留言说很不希望渲染身份问题,“不要搞受害者心态,教育出强者,就一切都好办!”不知是不是诗者深沉的嗓音,带她再次审视自己的坚强。此刻她却写道,“我忍不住流泪了。”

一位大学生嘉宾,兴奋地给朋友们发短信,“能想象吗,我在一个子女教育平台,听见‘妈妈’们讨论身份认同和模范少数族裔问题呢!”

这是耶鲁学生黄艾琳高中时写的诗。2020年夏天,艾琳曾经发表过一封写给美国华人社区的公开信,引起很大反响。艾琳从八年级爱上写诗,2015年她根据自己去中国留学的经历创作了《交融》和《钢琴》两首诗,获得美国年轻国家诗人称号,由奥巴马总统夫人在白宫亲自颁奖,并聘为学生文化特使,在各地高中推广诗歌文化教育。高中期间,艾琳多次在美国和英国获奖,并应邀在林肯中心等地表演自己的作品。她的诗歌作品主题,大都集中在身份探索、种族平等和文化交融上。黄艾琳目前在耶鲁大学主攻英文专业,并创建了诗歌俱乐部。

艾琳的母亲说,第一次读到这首诗,眼泪就止不住。好像二十多年的游子漂泊之心,被女儿的诗,轻柔地触摸了一下。反思年轻人对身份的探索中,如果缺乏了父母的理解和陪伴,他们是多么孤独。华人移民一代注重的情商育儿(EQ parenting),不应该只是关门带好自己的孩子,还包括促进社会多元化进程,让孩子的将来,有更平等的机会,更丰富的阅历。

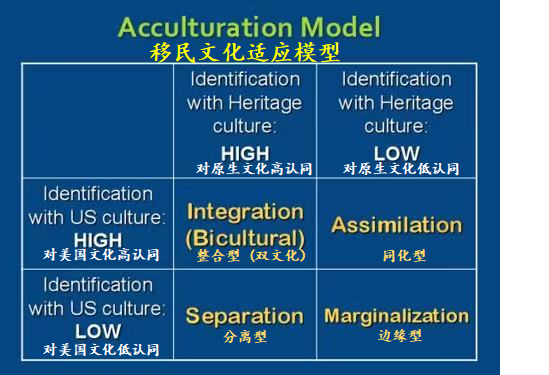

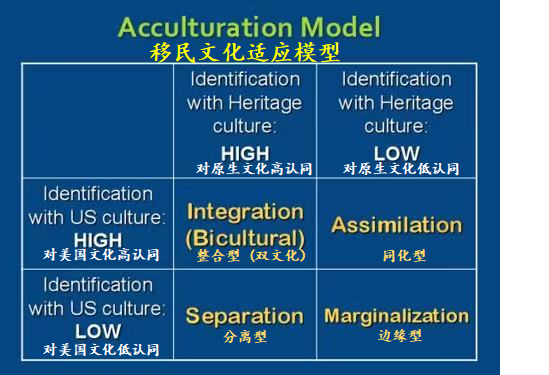

华裔中西文化之间的身份认同,到底走怎样一条路更好?加拿大心理学家John W Berry在他的多元文化心理学中建立了一个模型,提出同化(assimilation)和交融(acculturation)的关系。

当我们同时具备对中国原生文化和美国文化的高度认知时,我们一方面可以自如地向社会展示华人文化,同时也能自主地吸收美国的历史人文。这种积极的文化整合(integration),赋予我们双重文化(bicultural)的自信。如果我们对两种文化都缺乏深切的自我认同,就容易被边缘化(marginalization),可能永远都是异乡人。如果父母缺乏对美国文化的学习,只强调孩子继承华人的优秀品质,在发生文化冲突时,可能就会怪孩子太理想主义太激进,那就是自我分离(separation)。一味地崇尚美国文化,放弃和排斥自己的原生文化土壤,追求同化(assimilation),不真正建立牢固的自我认知,也不是追求个人幸福的途径。

John W Berry的理论模型,给移民家庭教育提供了可行的指导。在美国的移民父母和中文学校,可以多向孩子传递原生文化的自信,同时积极学习美国的人文思维;在美国的华二代,可以多向父母传递美国文化历史知识,同时倾听父母的故事,耐心陪伴他们走过内心的文化整合历程。

两代人彼此看见,是文化交融和身份探索的第一步。路还很长,愿华人代代携手开创!

“说 pillow, pill [pil], pill ”pillow, pillow, pill, pill,

ON FORGETTING HOW TO SPEAK MANDARINMy second grade teacher pries my throat openand forces me to say the word pillow. Say it,she says, pill-ow. Pill. Pill, like somethingthat can cure my un-american illness. And I say backpell-ow. The way my parents say it. The laughter in the roomchokes me-i can't speak without the vowels stilling the air,without the syllables strangling my tongue. At home,I practice saying it in front of the mirror, pillow, pillow, pill,pill, like chanting the words to a song that I don't know by heartbut I know that the English language is so rigid-shapeless, an ocean without wax or wane, onlyright or wrong: You can't speak half-ying yuand still be full American. You can't say leggings like leggywhat my mother does before the ladyat the mall yells at her to speak English, please-my mother who says Easter like Esther, who doesn't knowshe from he sometimes, we shop for anything thatcan pare the skin off our bodies, for a knife to cut off our mothertongue, and sometimes, Mandarin flows back to me inscraps of burning paper, in the lines of that song on the radio whosechorus is the only part I remember that ancient poemthat my mother once recited to me:举头望明月,低头思故乡。I am beginning to think Mandarin is a myth:They say in China my mother spoke as if her Mandarin could cleavevalleys through mountains, could steal waves from the oceans. In Chinamy mother commanded language as if it were an infantryand she was so large with words that everyone called her goddess. In Americamy mother is shrinking, is brandishing silence as a shieldand everyone calls her chink—I know that language is disguise,and the more Mandarin I forget the more American I become.,tongueand trust me, i'm so good at forgetting: I scrape sonnets off myto seem more American. As a child, I stopped talkingto see if that would make me an AmericanI silence my mother so that I am an AmericanI am eighteen years old and I still don't know how to speak-- but I know that language is a weapon,that I can hold it to my parents' throatsto force them to speak American, please, to stretch their o'sand lower their e's, to quell the rapid waterfall of Mandarinthat threatens to burst from their mouths butMother, even after all these years, I am still so bad at EnglishSometimes I say soot like suit. Sometimes I don't saywords I can't pronounce. Sometimes I mistakea lost language for a dead thingconfuse silence for fluency. Sometimes, I returnall the skin to my body and still feel lessthan whole. Once. I stood in frontof the mirror and said pellowpellowpellowto bring the dead girl back. Last night,I tried writing my Chinese name until I realized thatI had forgotten where to place each dash,where to bury each bone of a language I once knewMother, if a language dies and no one is around to mourn it,does it make a sound? I am trying to pull the silent things out of my mouth. Mother, do you remember when grandfather died an ocean awayWhen you handed me the phone to speak to my relatives,and I didn' t know how to say: i'm sorry?I thought of you, how sometimes I hearthe poems you'd sing to me:举头望明月,低头思故乡(Looking up, see the moon. Looking down,remember the home I've lost.

追踪美国热点时事新闻。

图文解说,美华快报让您握紧时代脉搏。

撰文:月下谷堆

编辑:Jing

本文由作者授权原创首发在《图解美国》公众号

微信公众号:TuJieUSA

微博:@华传媒

网站:ChineseAmerican.org

投稿/转载:[email protected]

推特:https://twitter.com/HuaMedia1

电报频道:https://t.m/ChineseAmericans

评论

加入讨论

请登录后发表评论

还没有评论

登录成为第一个评论的人。