【Chinese Version】

Authors: WeChat Project contributors

With the holiday season in swing and families reuniting (virtually and in-person), The WeChat Project is publishing some reflections from young Chinese Americans and Asian Americans. Together, we reflected on navigating intergenerational conversations and relationships this season. Here is what we have to say:

Amanda, 22, Texas

Since returning home from college due to COVID-19, I’ve been living with my parents for the past 9 months. Growing up as a loud leftist, queer, agnostic, 1.5 generation Chinese American, I was constantly ostracized and criticized by my vanta-white classmates, Baptist Christian church full of religious right supporters, and conservative parents. 4 years ago, I moved to a college 1,000 miles away to get as far as possible from my family and hometown in Texas.

Yet, to everyone’s (and my own) surprise, I began to empathize with my parents and defend the South more in college. I’d tell my classmates, most of whom are from the Northeast and West Coast: “Don’t perpetuate the myth of Southern Exceptionalism. Racism, sexism, homophobia, etc don’t just thrive in the South, but in all of America. NYC is one of the most segregated cities, and voting patterns show that across the nation, rural areas largely vote red and urban areas blue, but gerrymandering and voter suppression have been crafted into an art in the South.”

In both 2016 and 2020, my parents voted for Trump and other Republicans, not because they prioritize low taxes and other economic policies that benefit the rich—as many middle and upper-class Chinese Americans do—but because they have been strongly influenced by their churches, childhoods, and communities to loyally support the right and vehemently fear the left. For the past 4 years, I’ve been working on seeing from my parents’ perspective: I took history classes on 20th century China and the American South, interviewed my parents to learn more tangibly all they went through to immigrate to and survive in a new country, and asked my grandparents about my parents’ upbringing. I only wish that they would make the same effort to understand my point of view.

While I want to continue to talk with my parents about Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ+ rights, feminism, socialism, and more, I’m tired of fighting. Being an only child and with the rest of our relatives still living in China, my parents are all the family I have, and vice-versa. Especially as my parents grow older and my visits home grow shorter—besides this COVID-induced exception—I feel an urgency to prevent our disagreements from dominating our precious time together, so I’ll admit: right now, I often let our differences be. As I continue to be pulled in this tug of war of just wanting peace at home but also recognizing the importance of difficult intergenerational conversations, I hope to reignite them in a loving yet productive way in the new year.

Claire, 19, Connecticut

I am home already, and it’s been good! I’m finally able to take time to breathe and reflect and pursue old hobbies I didn’t have time for before, and I’m thankful. I don’t think much is going to change regarding conversations with my family—as a rule we are already very politically minded and my parents are slowly becoming more left-leaning and listening to the views of young progressives (being already very liberal and hardcore Democrats). I have been talking about politics, Black Lives Matter, and family history more with my grandparents, too. I hope the next couple of months and the new year continue to foster these conversations so that the momentum for change can progress.

Goose:

I’ve been home since Thanksgiving. Before I went back, I was already dreading any conversations about the election or politics. China’s influence on Hong Kong, where my family is from, and the relationship between China and the US has turned my family into staunch Trump supporters and adopting far-right views. It’s extended beyond an ideology into a way of being; conversations in and among family are almost exclusively about politics, my mom constantly listens to key opinion leaders pushing far-right views and conspiracies, even at the dinner table.

As a millennial raised in the US, I wasn’t alive to watch the rise of communism in China, or experience life under colonial rule in HK. And it’s this generational gap that often gets used against me for harboring progressive views, such as supporting BLM or stimulus checks, that get misconstrued as “communist.” I don’t disagree that my world view is still small. But I think that being a first-generation Asian American has put me in a position where the world doesn’t have to exist in black and white, where I can critique America and still say that there’s merit to living here. For the time being, I’ve largely set aside attempts to introduce my own perspectives. Instead, I’ve been engaging in conversations about the lived experiences of my family, trying to untangle the mass of anger, fear, and colonialism that has led them to this point. Maybe I will never be able to fully understand their experiences, but trying to bridge that gap is a start.

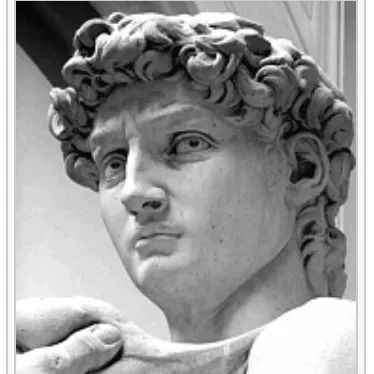

Image credit: Lia Johnson

Alana, 17, Illinois

Because I’m not “going home”, I don’t have particular feelings about that. However, I am a bit apprehensive about discussing current events matters because my parents and us kids (a 24-year-old, a 17-year-old, and a 14-years-old) have different opinions on many controversial topics, particularly the Black Lives Matter movement and the election. Something interesting we’ve been discussing lately is the abundance of Chinese immigrants (middle aged and up) who voted for Trump and how the online Chinese community is reacting to Black Lives Matter and the election. My mom has also mentioned that many people, despite being very well educated, are spreading ideas of voter fraud that are blatantly false, so I plan on asking my parents more about why so much of the Chinese community is willingly backing Trump.

Tiana, 19, Illinois

When my Chinese American friends and I talk about family, it’s almost always about the pandemic, about anti-Blackness in our community, and about right-wing disinformation on WeChat. We rollercoaster between a frustration so hot it boils tears and a goal to make drastic changes.

My second-generation friends are ambitious in their plans to reframe and reimagine, to build a near future where pandemics don’t kill along the lines of race and poverty and the response to economic recession and geopolitical tension is not more racism.

But when I’m with my parents, they look at these problems, they shake their heads in Chinese and they carry on. “Where will the money come from?” “How will any plan pass?” “No one in this country will care.” My parents do not patronize my ambitions. But when I spend all my waking hours with their concerns, won’t I forget my most radical dreams?

Louise, 21, New York

It’s a weird holiday season. I’m going home to my mom and brother, but in a way, family reunions this year won’t be very different from my semester so far – instead of three different WeChat boxes in our video calls, there’ll just be two, one from my father who works in China. Actually, thanks to WeChat, this pandemic of social distancing and quarantines has brought our family closer than ever before. Time alone in my apartment means I’ve video called the parents during dinner (so often they sometimes don’t pick up) and pictures of our meals are sent in the group chat as a nightly check-in. The sheer frequency of video calls amidst pandemic fatigue has led to deeper conversation beyond “how are your classes?”, and our family has even been able to learn US history together (the stuff they don’t tell you in textbooks). Even though our family is apart this year, we have a lot of reasons to celebrate, including the election results and my mother’s first vote as a US citizen (!). This year, the political rants have flipped; I’m excited to hear from my mom’s experiences engaging with *her* friends from the opposite political spectrum. But, whatever the topic, whether it be my brother’s SAT or the new presidency, I’ll definitely be making sure the festivities are done over our favorite WeChatted dish.

Giselle, 21, California

I didn’t go home for Thanksgiving.

I was sent home from school in March, and didn’t leave until I returned to school in late August. It was the longest I’d ever been home since high school. When I think about why I decided to stay at school for Thanksgiving, I think about how I used to dread extended family gatherings, even before COVID had started. I think about the uncomfortable conversations I’ve had with my pot-bellied uncle, who works as an engineer and immigrated from Taiwan in the 1990s. My mom suspects that he voted for Trump, but no one has ever directly asked him about it, because no one wants to have that conversation.

My first winter break back home from college, we visited extended family for a holiday dinner, like we always did.

“How’s the food at college?” my uncle asked.

“Not bad. Not everyone likes it, but I think it’s fine.”

He smiled widely at me. “You must enjoy the food at your school, huh?” He continued to stare at me, making vague motions around his face with his right hand. Suddenly I realized he thought that my face had gotten fat, that I must have enjoyed the food at my school a little too much. I laughed weakly and didn’t say anything back. I looked back down at my dinner and wondered how much of it I should eat.

Earlier this spring, I had a thirty-second conversation with him during an extended family Zoom call. He asked what I’d been up to since coming home from school; I told him that I was currently baking muffins for Mother’s Day.

“Haha, it looks like you eat a lot at home,” he said. He cleared his throat. “Exercising is important! Everyone, let’s make sure to exercise during quarantine.”

My mind went blank with rage, irrational shame, and my lack of Chinese skills. I opened my mouth to respond, but nothing came out. How had nothing changed in three years?

During the week of Thanksgiving, I sat in on another family Zoom call, this time from my dorm room three thousand miles away from my family. My uncle announced he had a question for me. I plastered on a smile for my laptop camera and hoped my face didn’t look too fat.

“Are you still writing your articles?”

I froze. This past summer, after one particularly tense family Zoom conversation about affirmative action and Black Lives Matter, we’d spent the next two months arguing over email—I sent him long documents filled with links to academic studies, he sent back personal anecdotes from his immigration to America. I’d told him that I had joined the WeChat Project, because it seemed like there were a lot of young Chinese Americans like me who were struggling with similar conversations with their families. Then the school started back up again, and we stopped exchanging emails.

“I—yes. I’m still writing my articles.”

“That’s good. Can you send me the link? I’m curious about your generation’s perspective.”

“Oh. Yes! Yes, absolutely, I’ll send you some of the stuff we’ve been writing.”

I might have a fat face, but at least now I have a fat face with a perspective worth listening to.

—-

This article is part of The WeChat Project, an initiative led by young Chinese Americans committed to bringing progressive perspectives to the Chinese diaspora. You can continue following our work on our website (thewechatproject.org), Facebook (@thewechatproject), Instagram (@thewechatproject), and Twitter (@wechat_project).