Black Chinese relations: the story of my family, one of the oldest Chinese families in Texas

by Shannon Prince

Preface:Much of the discourse has come from first- and second-generation Chinese Americans, but my family comes from the first generation of Chinese Americans – my ascendant left Hong Kong to build the railroad, married a freed slave-woman, and fathered one of the oldest Chinese families in Texas. Grandfather Lee was a leader in the first Chinese Texan community, and he upheld a firmly anti-racist ethos. At this time of racial tension, I wanted to share his inspiring vision for what he dreamt of our community being.

________________________

In the context of the conversation about Chinese American attitudes to Black Americans that has become amplified and more urgent in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, many have spoken from the perspectives of first- and second-generation citizens. At times, the conversation seems to revolve, as inexorably as a planet, on the axis formed by those two poles.

I have another perspective to offer.

I speak not as a first-generation immigrant but as a scion of one of the first generations of Chinese immigrants to America. I come from one of the oldest Chinese Texan families. And I’m Black. And in this moment, I can feel my ancestor Grandfather Lee urging me to speak:

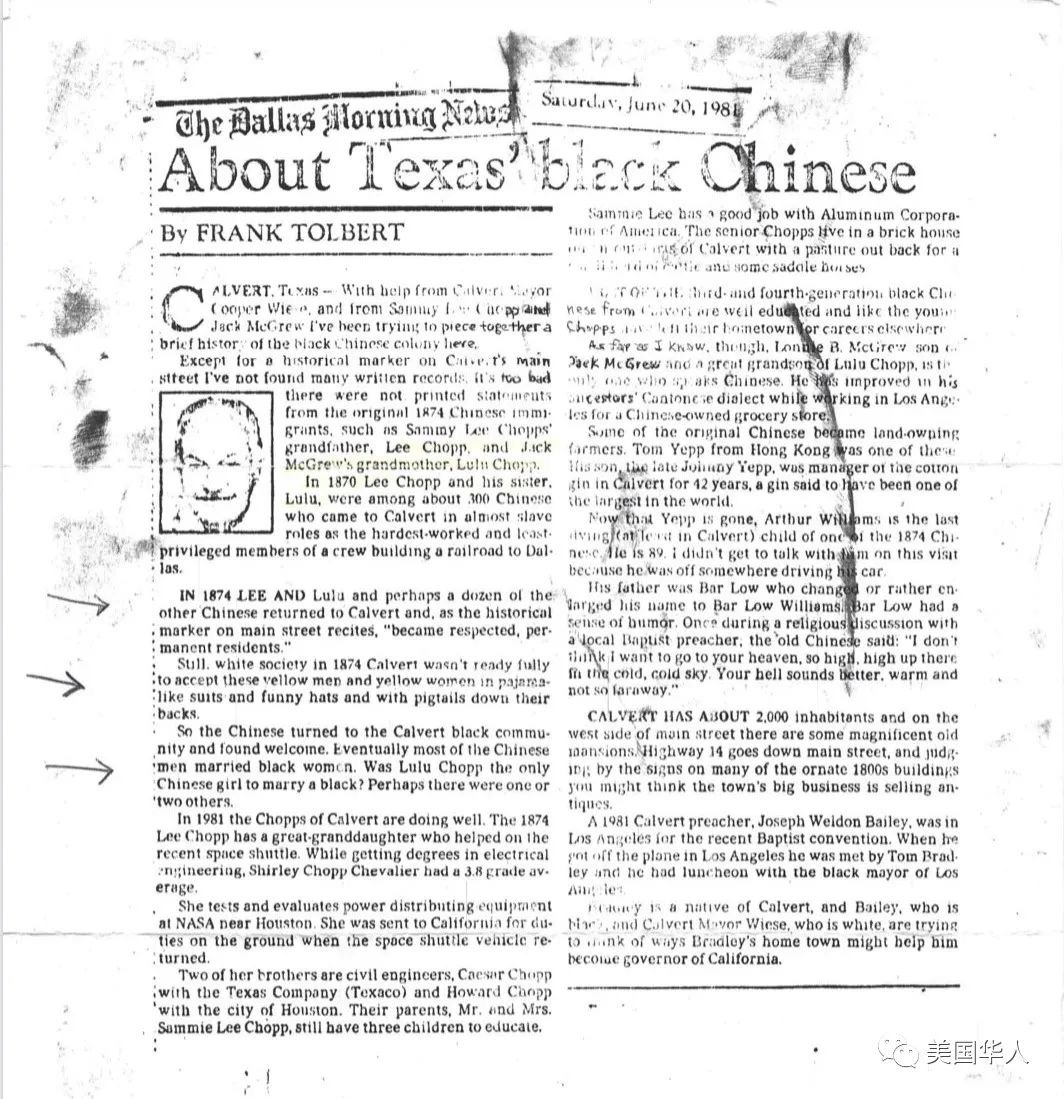

Grandfather Lee left Hong Kong for America in the mid-nineteenth century to labor on the railroad. He arrived in the port of Galveston, Texas with two hundred ninety-nine other Chinese men as well as a woman – my aunt, the first Chinese woman ever to journey to the state. When their ship landed, Grandfather Lee and my aunt found themselves facing crowds who had gathered at the shore to see Asians for the first time as well as a newspaper reporter there to document for posterity the history-making journey(*). But the racism the Chinese laborers faced was so brutal, that after their job concluded, most returned to their homeland. Grandfather Lee remained in Texas, though… he had fallen in love with a freed slave-woman.

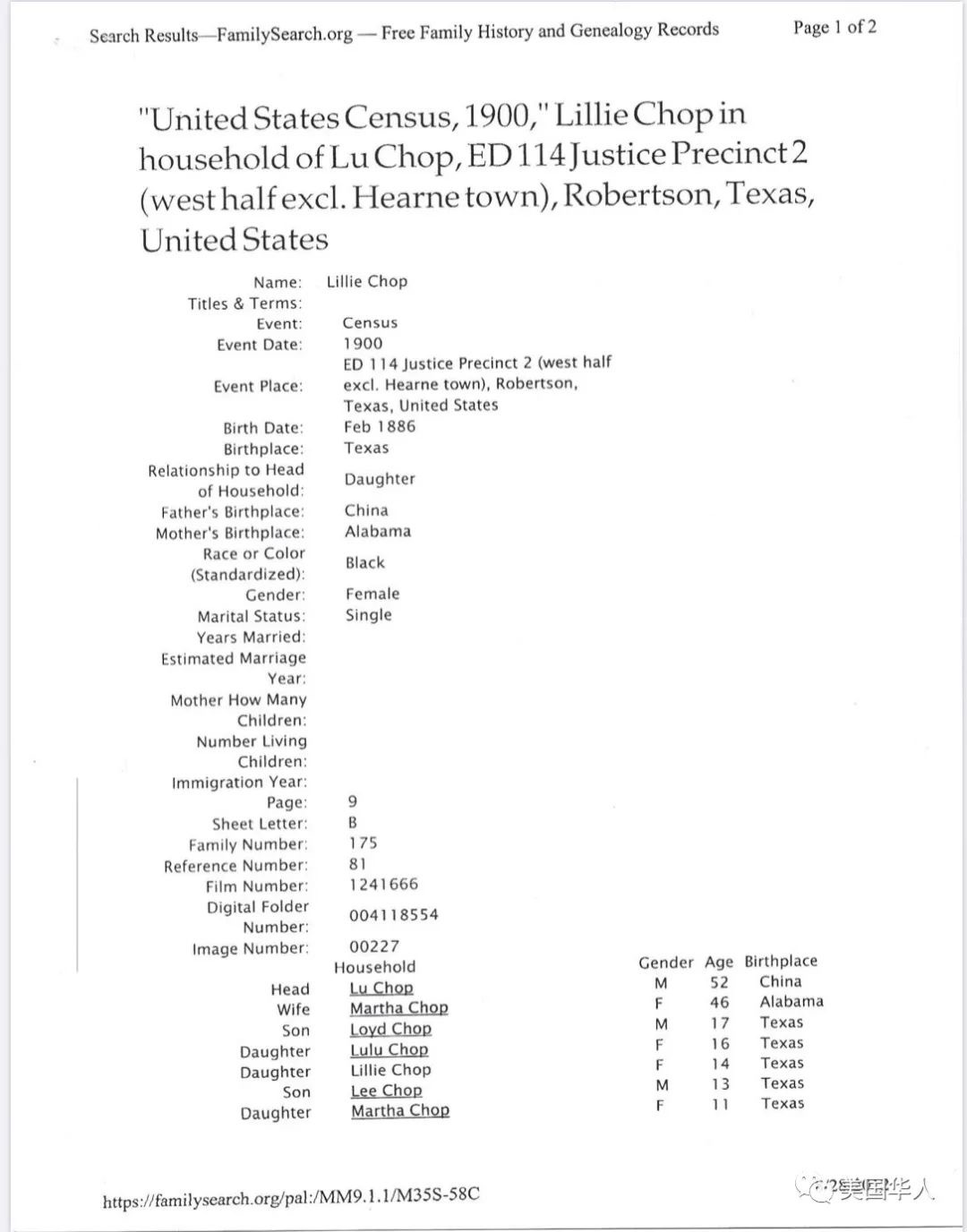

A few other men remained with him. One was in love with a white woman; another two, with formerly enslaved Black women – one of whom, Moriah, was the sister of the lady with whom Grandfather Lee was so enchanted. My aunt never returned to China either – she had given her heart to a Black freeman as well. The five couples married, but per family history and research, the Chinese gentleman and his white wife, like my aunt and her husband, never bore children. Thus, three of the foundational families of Chinese Texans -- the Lees; our cousins, the Yepps; and the Williamses (immigrant Bar Low took his wife’s surname) -- are all Black. Many of the first “second-generation” Chinese Texan children were Black children.

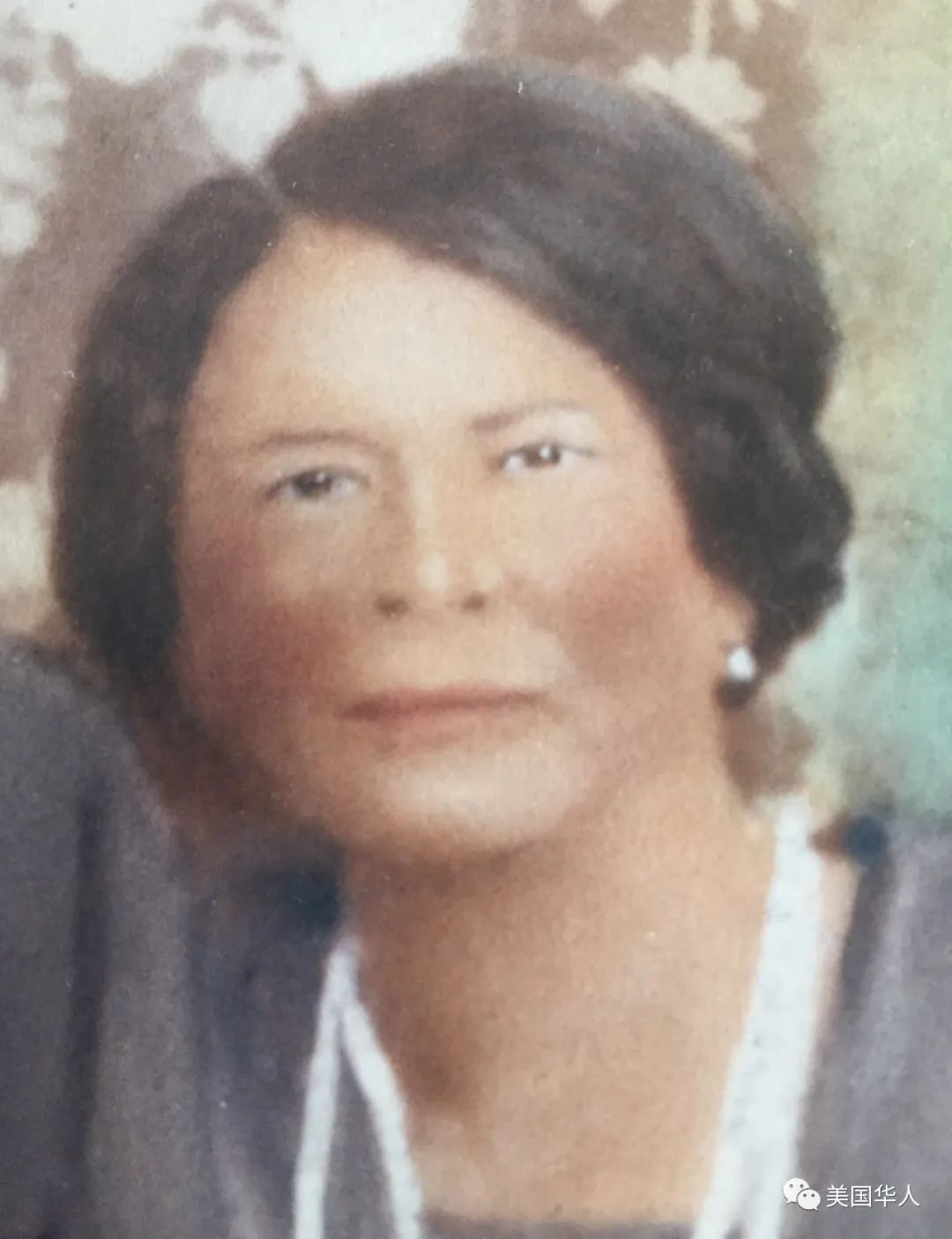

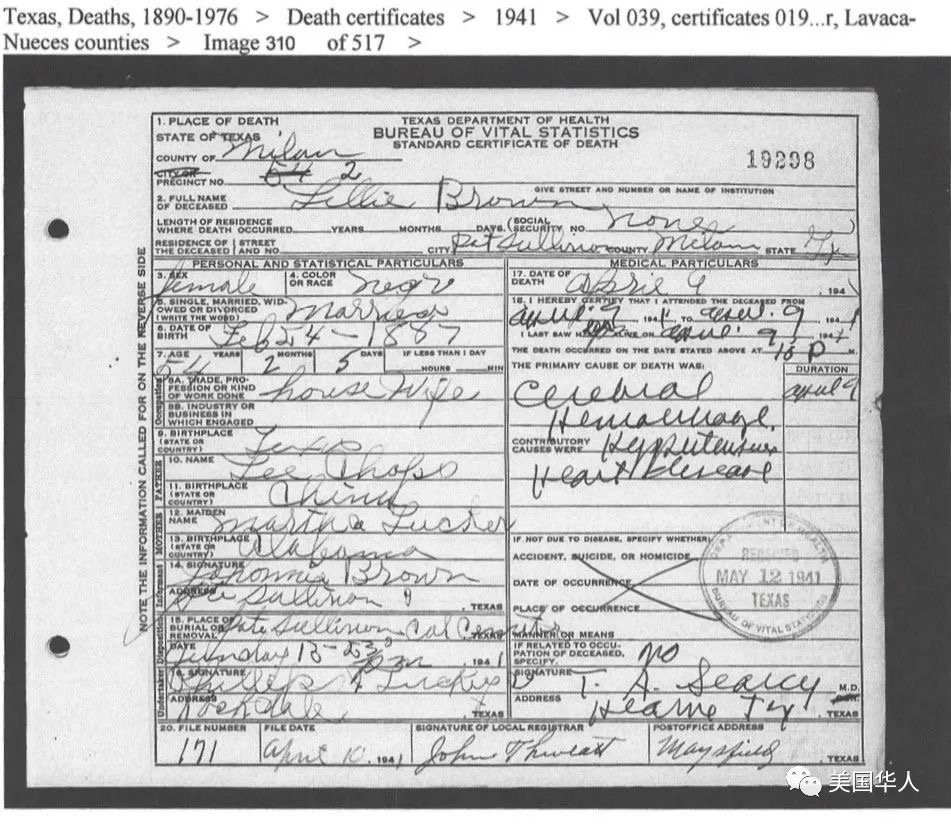

Grandmother Lillie, Lee and Martha’s daughter, author’s ancestor

Lee and Martha’s son, Lillie’s brother

Almeta Prince,Lillie’s granddaughter, the author’s grandmother

Eventually, other Chinese settled in Texas forming a community that Grandfather Lee led, and he led it with an explicitly anti-racist ethos. Even in that era, white supremacists framed Chinese Americans as a model minority in contrast to African Americans, though the stereotypes of the races were the opposite of what they are now: African Americans were demonized for being too upwardly mobile; Chinese Americans, praised for knowing our place and not seeking to upturn the racial hierarchy. Now, of course, Chinese Americans are celebrated for our stereotyped upward mobility while African Americans are castigated for lolling about the lowest stratum of the nation. In truth, both races, in every era, have sacrificed and worked hard in the hopes that they and their children would and will live with dignity.

Grandfather Lee rejected immoral rhetoric. He was too smart to let white supremacists pit him against another minority group he could be coalition-building with, too savvy to be fooled into thinking that racist narratives ultimately serve anything but white privilege. He and his wife, Grandmother Martha, fell in love, in large part, because they empathized with each other’s struggles. They looked at each other and saw sublimity where others perceived only sub-humanity. At their farm, they hosted both cakewalks (traditional African American dances) and lantern kite launches for their neighbors, welcoming people of both Asian and African backgrounds to celebrate their dual traditions. That’s the Chinese American community Grandfather Lee founded. That’s the one he envisioned continuing throughout the centuries. And that’s the one we often are. And yet, it’s also the one we sometimes aren’t.

No Chinese Americans worked under crueler conditions, suffered more racism, or had less legal protection than nineteenth-century Chinese Americans. The struggles of those ancestors – and the civil rights protections achieved through movements spearheaded by African Americans – are the foundation of our current Chinese American community. Yet when my family tried to visit the renown Lee Family Association in Chinatown, San Francisco, people rushed to turn locks as though my sexagenarian parents and I might rob them, shooing us away with the counsel that “this is not a Chinese restaurant if that’s what you’re looking for.”

One of Texas’ original Lee families was not welcome at the Lee Family Association.

Lately, I’ve seen Chinese Americans call upon others in our community to acknowledge that America was built from the bones of African American slaves (upon the graves of Native American genocide victims), a call that is sometimes rejected with the rebuttal that “Chinese Americans built the country,” and thus, the African American case is not unique. But as a child of both the railroad and the cotton field, I know that the work Grandfather Lee did, though grueling, does not compare to that performed by Grandmother Martha as a slave. Grandfather Lee came to this country by choice to do paid work. He did not have to fear overseers with whips or rape. He was free. He wasn’t sold away from his parents before they could teach him his heritage – I know my Chinese family name. I don’t know my African one. I don’t even know from which country Grandmother Martha’s ancestors were.

That’s the difference.

That’s a very, very, small sliver of the difference.

Fannie Lou Hamer, an African American civil rights activist, once arrested for trying to eat at a whites only café and then taken to prison where police officers beat her for not addressing them as “sir,” sexually assaulted her, and then forced prisoners to beat her nearly to death once said, “I don’t want to hear any more talk about ‘equal rights.’ I don’t want to be equal to people who raped my ancestors, sold my ancestors, and treated the Indians like they did. I don’t want to be equal to that. I want ‘human rights.’” Grandfather Lee didn’t want to be equal either to the whites who regarded him as good enough to break his back building a railroad to connect their country but not good enough to be a citizen of it. Nor did he have the slightest interest in being considered a “model” by those who thought it fit to enslave his wife. He envisioned a different America. And at this moment in our history, it is my responsibility as one of his lineage-bearers to stand up for that vision.

I am inspired when, we, as Chinese Americans -- as Asian Americans -- are the people Grandfather Lee dreamed we would be, such as when Annie Tan, niece of Chinese American hate crime victim Vincent Chin, called upon Chinese Americans to stand with Akai Gurley, an innocent, unarmed Black man shot to death, and not with Peter Liang, the Chinese American officer who killed him, urging us not to yearn for the day in which our officers can wrongfully kill Black people with the same impunity as their white counterparts (**). I see it when Youa Vang Lee, the mother of Fong Lee, a Hmong man killed by the police, urged Asians to stand with Black people in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death even though one of the officers charged with adding and abetting in the killing, Tou Thou, is Hmong. In a speech, she reminded her community that after her son was killed “black people were with us the whole time, morning or night. Whenever we needed something, they were there, even up until 1 in the morning.”(***)

- called upon Chinese Americans to stand with Akai Gurley, an innocent, unarmed Black man shot to death, and not with Peter Liang, the Chinese American officer who killed him, urging us not to yearn for the day in which our officers can wrongfully kill Black people with the same impunity as their white counterparts

This is about more than being a good ally to Black people. It’s about being good ancestors to our Chinese American descendants. I have honorable stories to tell about Grandfather Lee.

What kind of stories will your descendants have to tell about you?

*Irwin Tang discusses my family in his book Asian Texans: Our Histories and Our Lives.

** https://medium.com/listen-to-my-story/peter-liang-was-justly-convicted-he-s-not-a-victim-says-this-niece-of-vincent-chin-739168c9c944#.y109e5ilt

***https://nextshark.com/fong-lee-minneapolis-cop-blm/

___________________________

Shannon Prince is an attorney. She earned her bachelor’s degree magna cum laude from Dartmouth College, her master’s degree from Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, her law degree from Yale Law School, and her doctorate from Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. She is a member of her firm Boies Schiller Flexner’s

Asian American & Pacific Islander Affinity Group as well as the Asian American Bar Association of New York and the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association. Her book on tactics for creating racial justice in the workplace and the community is forthcoming from Routledge.

评论 3

加入讨论

请登录后发表评论

Jean Thornell

确认操作

Shun J

确认操作

Kelly chopp

确认操作